Dear Colleagues,

Thanks to the extraordinary effort of the two committees on the CHUS Academic Excellence Award and the CHUS Distinguished Service Award respectively, the CHUS Board has approved their recommendations and thus announces the winners this year. Please find the citation for each of the awardees in the two attached documents.

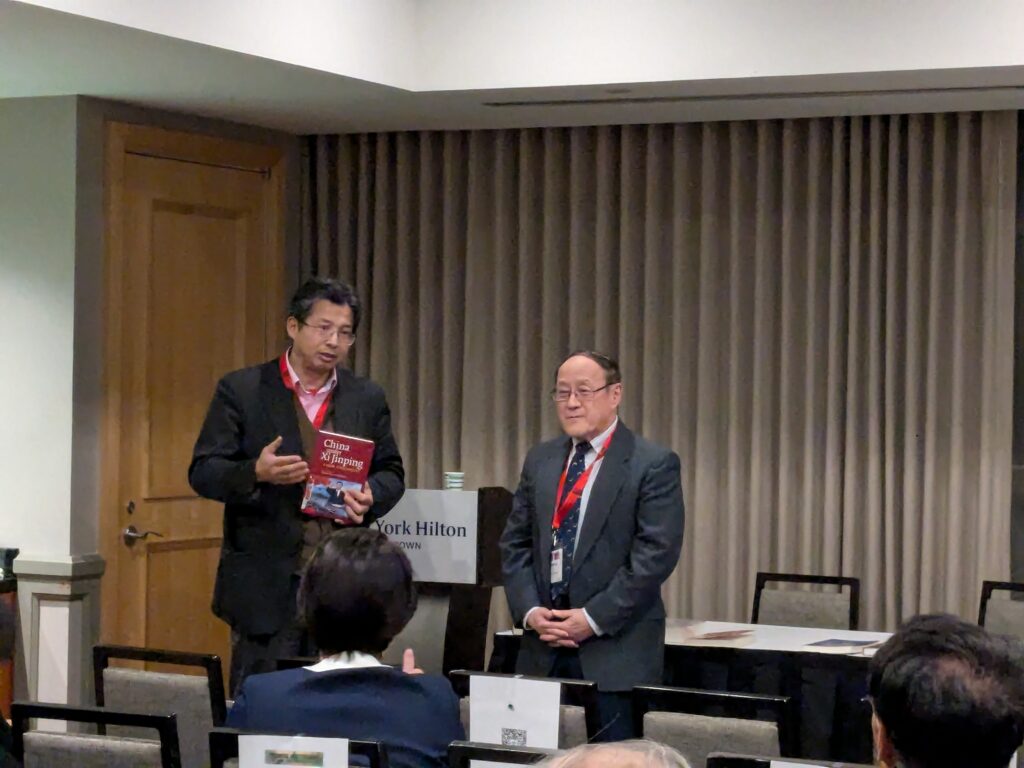

CHUS Inaugural Lifetime Achievement Award: Professor Hanchao Lu and Professor Xi Wang.

CHUS Academic Excellence Book Award: Professor CHEN Jian’s monograph — Zhou Enlai: A Life (Harvard University Press, 2024).

The Honorable Mention: Professor Hanchao Lu’s monograph — The Shanghai Tai Chi: The Art of Being Ruled in Mao’s China (Cambridge University Press, 2023).

Graduate Student Research Travel Grant: Hong Song (third-year doctoral student, Stanford University). Dissertation: “The Insect Matters: White Wax, Environment, and the Society in Qing Southern Sichuan”

The other award categories are unfulfilled this year either because of the limited pool of nominations or the decline of modest nominees.

I would like to thank those who participated in the nomination process, and especially those who served on the two committees: Professors Yi Sun (Chair), George Qiao, Aihua Zhang, and Dewen Zhang on the Academic Excellence Award Committee; and Professors Shuhua Fan (Chair), Di Luo, Xiangli Ding, and Guolin Yi on the Distinguished Service Award Committee.

We on the CHUS Board are looking forward to celebrating the awardees and the many achievements of our members with you at the AHA.

Thank you and happy holidays!

Qin Shao

on behalf of the CHUS Board.

CHUS Academic Excellence Book Award

The 2024 CHUS Inaugural Lifetime Achievement Award goes to Dr. Chen Jian, and Dr. Lu Hanchao won the honorable mention.

The CHUS Academic Excellence Book Award: Dr. Chen Jian’s monograph — Zhou Enlai: A Life (Harvard University Press, 2024).

This 800-page biography offers a nuanced and compelling portrait of Zhou Enlai, a pivotal figure in modern Chinese history, the PRC’s first premier, and a world-renowned diplomat. Drawing from an impressive array of sources spanning China, the USA, Russia, and India, Chen crafts a comprehensive narrative of Zhou’s life, tracing his journey from his early years to his final days. By examining the paradoxes of Zhou’s character within the complex historical contexts he navigated, the author delivers a balanced and insightful assessment of this extraordinary statesman. Meticulously structured and expertly written, the book employs a longue-durée perspective to illuminate China’s dramatic transformation from the late Qing dynasty to the Mao era. A must-read for those interested in modern China, diplomacy, and international relations, this work stands as a definitive account of Zhou’s enduring legacy.

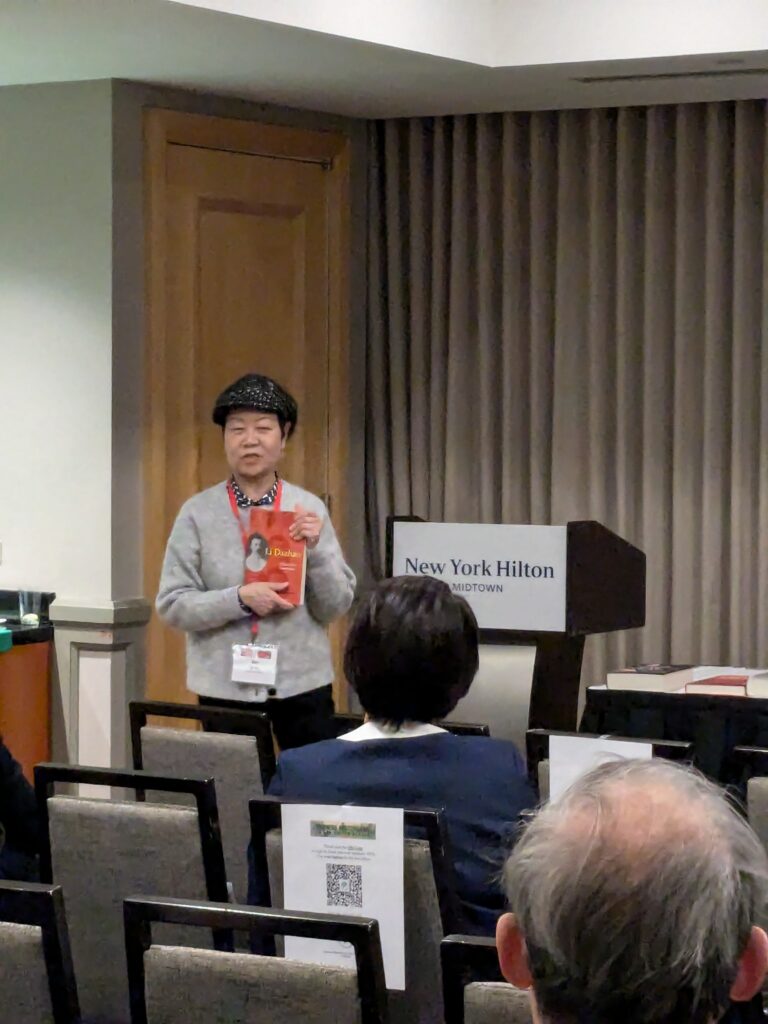

Honorable Mention: Dr. Hanchao Lu’s monograph — The Shanghai Tai Chi: The Art of Being Ruled in Mao’s China (Cambridge University Press, 2023).

Skillfully drawing from an extensive array of primary sources, Shanghai Taichi offers a rich and engaging narrative of the material world of the bourgeois under a politically adverse environment during the early decades of the PRC. It explores the intellectual contributions of the educated elites from the “old world,” the youth’s engagement with taboo literature, and the rise of women as a workforce, highlighting how women interpreted and enacted their visions of “liberation.” The work challenges the conventional demarcation of Mao’s China and the reform era by portraying the country’s economic rise over the past four decades not as a departure from Mao’s China but rather a drastic continuation of human behavior. The book seamlessly balances rigorous historiographical analysis with accessible and engaging prose, the book serves as a valuable resource for understanding the history of Shanghai, the People’s Republic of China, and the social history of communism.

Graduate Student Research Travel Grant

The 2024 Graduate Student Research Travel Grant goes to Song Hong, third-year doctoral student at Stanford University.

Dissertation: “The Insect Matters: White Wax, Environment, and the Society in Qing Southern Sichuan”

Song Hong’s project examines the importance of insect wax in understanding the social and economic lives in Qing-era southern Sichuan, a frontier region characterized by transregional trade and/or transnational exchanges of labor, knowledge, and profit. Hong’ proposal isdetailed and thoughtful, containing information on the relevant historiography, methodology, and significance of his study as well as the justification for the need to conduct further archival research in Beijing and Sichuan.

2024 CHUS Inaugural Lifetime Achievement Award

The 2024 CHUS Inaugural Lifetime Achievement Award goes to Professor Hanchao Lu, School of History and Sociology at Georgia Institute of Technology, and Professor Xi Wang, Department of History at Indiana University of Pennsylvania.

Professor Hanchao Lu

Professor Hanchao Lu has exceeded the criteria of excellence in historical studies and generosity in service. Professor Lu’s service to CHUS has been extraordinary. As the CHUS President (1999-2001), Professor Lu led a group of CHUS members for a successful visit to Taiwan in 2000 and published an edited volume: Modernity and Cultural Identity in Taiwan (World Scientific, 2001) after the trip. At the turn of this century, the Chinese Historical Review suffered two three-year hiatuses until, in 2003, when Professor Lu took the initiative to revitalize the journal with two colleagues. He served on the editorial team and then as co-chief editor for an unprecedented total of fifteen years (2004-2019) and helped to establish Chinese Historical Review (CHR) as a highly respected academic journal. Professor Lu has continued to support CHR as an author and CHUS for many of its activities.

Professor Lu has published nine scholarly monographs, three of which won awards, and numerous articles in major academic journals. From his first monograph in English, Beyond the Neon Lights: Everyday Shanghai in the Early Twentieth Century (University of California Press, 1999/2004) to the most recent one, Shanghai Tai Chi: The Art of Being Ruled in Mao’s China (Cambridge University Press, 2023), Professor Lu has engaged in cutting-edge study of everyday life that sheds light on larger issues such as modernity and state-society dynamics. Fittingly, Professor Lu has gained international recognition as a leading scholar in the China field with prestigious fellowship awards in the U.S., Europe, and beyond. He is also the editor of a sixteen-volume series titled The Culture and Customs of Asia and the co-founder of the China Research Center, an interuniversity center, in Atlanta. In these and many other leadership capacities, Professor Lu has significantly enriched the China studies field and promoted the understanding of Chinese history and culture in both the scholarly and public domains.

Professor Xi Wang

Professor Xi Wang’s longstanding dedication to CHUS is exemplary. As a founding member and the second president of CHUS, Professor Wang contributed to the establishment of CHUS as a scholarly society. During his decade-long tenure as a lead editor of the Chinese Historical Review (2003-2014), Professor Wang’s tremendous effort helped transform CHR into a highly reputable academic journal. Professor Wang co-edited Discovering History in America and Teaching History in America, two memoirs of CHUS members published by Peking University Press that solidified CHUS’s reputation as an influential overseas academic organization among Chinese readers. In fall 2024, Professor Wang digitized the CHUS archives from its pre-internet age, about 50 PDF folders and a total of more than 7,000 pages. These files cover the founding of CHUS and its first decade and are highly valuable for the preservation of CHUS history and future research. Professor Wang completed this monumental project with his characteristically high standards and commitment.

Professor Wang has authored, translated, and edited more than a dozen books and published numerous articles in and beyond his fields of African American history, Civil War and Reconstruction, and American constitutionalism. His monographs, The Trial of Democracy: Northern Republicans and Blacks Suffrage, 1860–1910 (University of Georgia Press, 1997, 2012) and Principles and Compromises: The Spirit and Practice of the American Constitution (Peking University Press, 2000, 2005, 2014) are widely considered groundbreaking works in his fields. Professor Wang has helped shape the academic discipline of U.S. studies in China. He built institutional partnership between American and Chinese universities and academic organizations, which enabled American scholars to teach in China and Chinese students to participate in academic activities in the U.S. As a prestigious Changjiang Scholar, Professor Wang also taught U.S. history at Peking University for more than a decade and trained graduate students there in U.S. history. His contribution to U.S.-China educational and scholarly exchanges is unparalleled. In 2022, Professor Wang was honored by his colleagues at IUP as a Distinguished University Professor.