“China Under Xi Jinping’s Presidency (2012-2022): A Historical Assessment”

Hilton Union Square, Union Square 19&20

Chair: Jingyi Song, State University of New York, College at Old Westbury

Papers:

Media in China, 2012–22

Guolin Yi, Providence College

From Trade War to New Cold War: Popular Nationalism and the Global Times on Weibo, 2018–20

Mao Lin, Georgia Southern University

Xi’s Campaigns to Fight Pollution, Climate Change, and the COVID-19 Pandemic

Qiong Zhang, Wake Forest University

What Did the CCP Learn from the Past? An Analysis of Xi Jinping’s Dexterous Utilization of History

Patrick Fuliang Shan, Grand Valley State University

Comment: Lei Duan, Sam Houston State University

Panel Abstract

Xi Jinping started his presidency as the supreme leader of the People’s Republic of China in 2012. Precisely ten years have passed since his assumption of that vitally important position. Needless to say, his leadership in China and his influence upon the world beg our urgent historical interpretation. This panel features papers from four scholars teaching at American universities. By focusing on diverse topics, the four scholars will explore Xi Jinping’s significant role in leading one of the largest and most populous countries in the entire global community. The papers probe the sway of media in China, examine the relations between China and the U.S., analyze China’s environmental and pandemic control, and interpret Xi’s use of history for political maneuvers. Collectively, the four scholars demonstrate the new historical trends that have taken shape during Xi’s first ten years as the paramount leader of China.

Paper Abstracts

Guolin Yi “Media in China, 2012-2022”

Between 2012 and 2022, the Chinese government used a series of measures to consolidate its control of the media. This paper studies the media policies of China by focusing on two sides: what the CCP tried to prevent and what it tried to promote. On the one hand, it passed laws and regulations that prohibit private enterprises from newsgathering and broadcasting and adds a new ban on hosting news-related forums. It also consolidated the control over online commentaries by shutting down VIP accounts that stepped out of the line. On the other, print media and the main portal website like Sina, Sohu, and NetEase have been involved in the promotion of Xi Jinping’s cult of personality by highlighting his images and quotes. By looking at these measures, the paper demonstrates the status of media environment in China under Xi Jinping.

Mao Lin, “From Trade War to New Cold War: Popular Nationalism and the Global Times on Weibo, 2018-2020”

The United States and the People’s Republic of China have been waging what the Chinese social media called “an epic trade war in human history” since early 2018. This ongoing trade war has attracted unprecedented attention from all types of Chinese media. The paper examines how popular nationalism has evolved over time and shaped China’s response to the trade war, focusing on the influential Global Times and how it used the social media platform, Weibo, to frame the trade war. During the early months of the trade war, China’s response was largely defensive. The Chinese public opinion claimed China as an innocent victim of the trade war, initiated by a reckless Trump administration. Many, especially those in social media, were also optimistic, believing that the trade war would be over soon once the U.S. government came to its senses. After Washington imposed sanctions on Huawei, a popular Chinese high-tech company, the public opinion shifted to an offensive mode. Many now argued that America was not looking for fair trade policies but trying to block China’s rise as a global power. Furthermore, the Chinese popular nationalism started to argue that China’s model of development was superior to America’s liberal democracy. Other issues such as Taiwan, Hong Kong, Tibet, Xinjiang, and the South China Sea further confounded the bilateral relationship and led to the rise of popular nationalism.

Qiong Zhang, “Xi’s Campaigns to Fight Pollution, Climate Change, and the Covid-19 Pandemic”

The winter of transition from Hu Jintao’s administration to Xi Jinping’s witnessed an unusually intense and prolonged smog that blanketed an area of approximately 1.43 million square kilometers in China. Dubbed the “airpocalypse” or “airmageddon” by some expatriates in China, this smog event is said to have sent a daily average of 9,000 emergency visits to Beijing Children’s Hospital during its peak week, half of which for respiratory illnesses. The incident highlighted the profound environmental and public health challenges facing Xi’s administration. While inheriting a booming economy that had surged to become the world’s second-largest by 2010, the administration was also confronted with the severe consequences of such rapid growth: stark environmental degradation and significant human tolls. The Xi administration’s resilience was further tested with the outbreak of Covid-19, an unprecedented global pandemic in the past century, with the first known cases surfacing in Wuhan, China. This paper zooms in on how Xi and his administration coped with these crises, highlighting, on the one hand, areas of continuity between his environmental and public health governance and those of his predecessors, and on the other, the new coping strategies that have emerged as unique hallmarks of his leadership.

Patrick Fuliang Shan, “What Did the CCP Learn from the Past? An Analysis of Xi Jinping’s Dexterous Utilization of History”

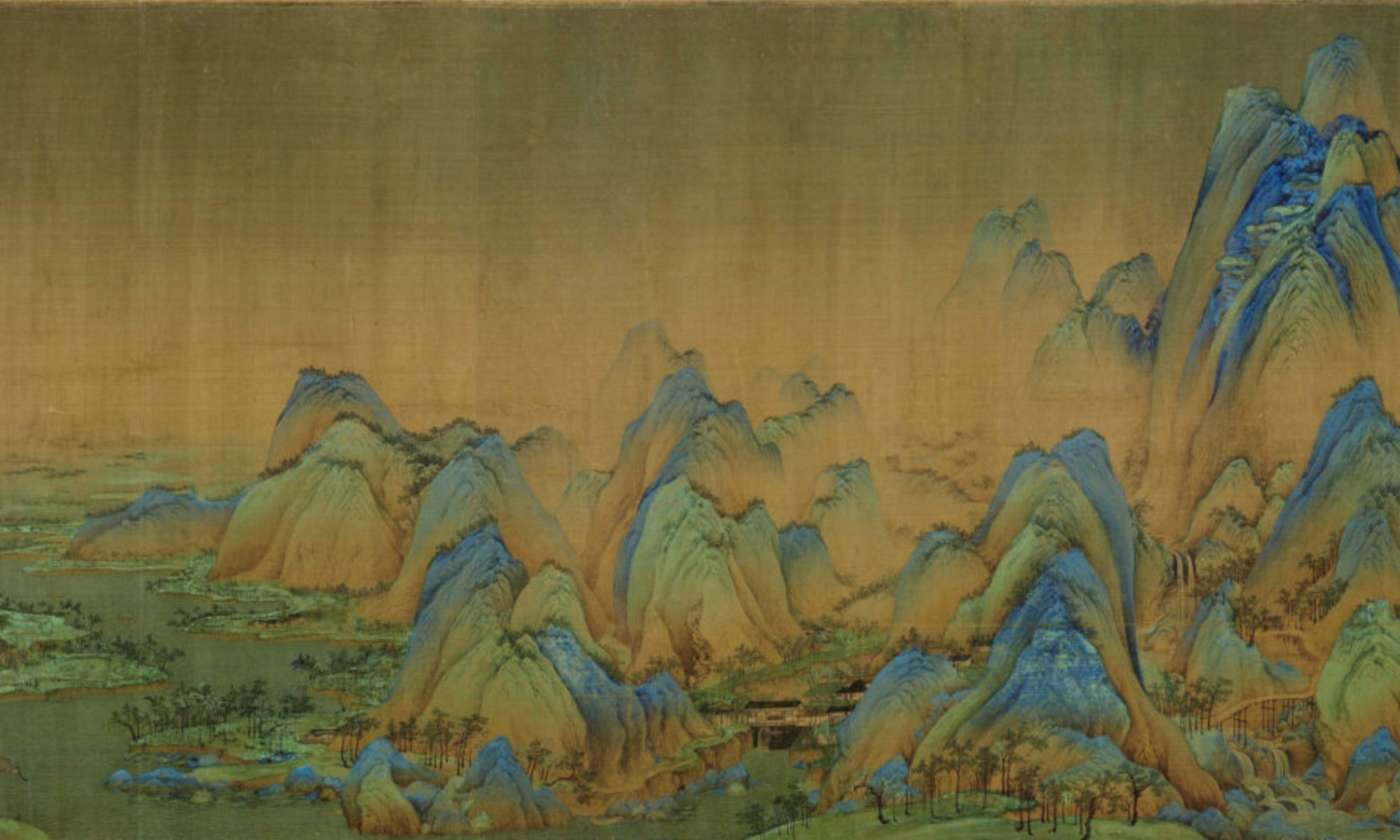

China is one of the longest civilizations in the entire world, and its historical resource is so rich that rulers in the past millennia have utilized it for their political maneuvers. Ever since Xi Jinping came to power in 2012, the CCP under his leadership has used this wealth of resources for initiating new political policies. Xi launched the revival of the Silk Road by adopting the Road and Belt Initiative. He called for the great resurgence of the Chinese nation purporting to restore China’s glorious history. He often led the Politburo members to visit the communist historical sites to reaffirm their oaths for defending the communist faith. Many of Xi’s new political terminologies are related to history. This paper investigates Xi’s intentions, strategies, and tactics of using history to legitimize his policies, defend his moves, and woo support to his regime.